Adrian Kavanagh (18 July 2010)

Recent polls from RedC and Irish Times/Isbos-MRBI have focused significant attention on the Labour Party and point to significant gains being made by that party, as tantamount to a “Gilmore Gale”. But the extent to which these significant shifts in support levels towards the party can be translated into seat gains sufficient to allow Labour challenge the traditional dominance of Fine Gael and Fianna Fail may be shaped by the party’s geography of support, which will be studied in this post.

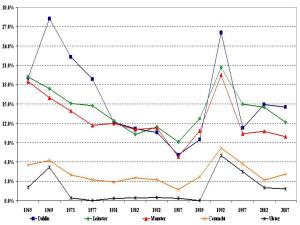

Labour Party support, since the foundation of the party in 1912, has traditionally been concentrated to south and east of line drawn between Dundalk and Limerick – this support base being associated with geographical distribution of farm labourer (large farms and arable farming) who proved (more so than the urban working class who tended to favour Fianna Fail) to be the party’s most relaible source of support in the early decades of its existence. The importance of familial dynasties in rural constituencies allowed for the continuance of this trend, e.g. the Corish family held a Labour seat in Wexford between 1921 and 1981, while the Spring family held a Labour seat in Kerry North between 1943 and 1992. Labour’s strongest regions, historically, have been Munster and provincial Leinster – these regions have proven to offer more reliable sources of Labour Party than Dublin, where the party’s support levels have fluctuated (often quite wildly) over the party’s history.

Since the amalgamation of Labour with Democratic Left in 2000, Dublin has emerged as the party’s constitently strongest region. In the 2007 General Election (when the national level of Labour support stood at 10.1%) Labour won 14.5% of the first preference votes cast in Dublin, as against 12.1% in the rest of Leinster, 9.9% in Munster and just 3.3% in Connacht-Ulster (where Michael D. Higgins’ Galway West vote accounted for almost half of the total Labour vote within this region).

In the local elections in 2009, Labour support nationally amounted to 14.7% of the first preference votes cast. (This was significantly lower than the Labour support levels recorded in the opinion polls taken prior to these elections, further underpinning concerns of an inability to maximise the electoral gains that Labour could expect to benefit from based on the growing popularity of the party and its leader, Eamonn Gilmore.) These support patterns marked the continuance of the growing urbanising trend evident since its amalgamation with Democratic Left in 2000; the party won 26.4% of the Dublin vote (a similar level to that won by Labour in Dublin in the Spring-tide election of 1992) while they also polled considerably higher than their national average in the other city council areas. Labour’s weakest constituencies tended to be concentrated in the Border, Midland and West regions, as in the 2004 elections, failing to contest any constituency in Roscommon and polling weakly in Monaghan (1.1%), Leitrim (1.5%), Longford (1.5%), Cavan (2.4%), Mayo (3.1%), Clare (4.0%) and Offaly (4.3%). The 2009 result had marked a 4.6% improvement on the general election performance nationally, but support levels in these areas appeared to be largely impervious to the party’s improving fortunes. Would these areas still prove resistant to the even more significant “Gilmore Gale” swing to Labour suggested by the recent opinion polls? Will the Gilmore Gale instead blow unevenly and range between a hurricane in some areas (e.g. Dublin) and a light breeze in other constituencies?

The experience of the 1992 Spring-Tide election is the only precedent that can provide some clues as to the potential geographies of a “Gilmore Gael” swing to Labour. Winning 19.3% of the national vote in this election, Labour succeeded in gaining 176,023 extra votes, more than doubling the number of votes the party won in the previous election (1989) and marking a 9.8% increase in its percentage share of the vote. What is notable about this election is the extent to which this increase in support was most pronounced in Dublin and the other urban constituencies, where the party’s share of the vote, on average, increased by 14.4% relative to an average increase of just 6.7% in the other, more rural, constituencies. The other most notable trend was of significant increases for the party in constituencies where the party had recruited high-profile left wing politicians, such as Jim Kemmy (Limerick East) and Declan Bree (Sligo-Leitrim), from outside the party ranks. It is also worth noting that some Labour gains in this election came in constituencies where the party was effectively starting from nowhere, having failed to contest that constituency, or else have polled extremely poorly there, in 1989; most notable examples here being the seats won by Willie Penrose (Westmeath) and Moosajee Bhamjee (Clare).

In many of the rural constituencies, and especially in the party’s traditional heartland areas in the South and South East, the extent of Labour gains proved to be less impressive. Indeed the party only gained 25 extra votes in Tipperary North and its share of the vote actually fell by 0.1% there. This could underpin the contention that rural Ireland may prove more resistant to a “Gilmore Gale”, mainly due to the fact that support trends in these areas tend to be less volatile than those in Dublin. However it is worth noting that many of the constituencies already had significant Labour support bases (with the notable exception of Longford-Roscommon where the Spring-Tide translated into a miserable 1.5% share of the vote) and indeed the party already held seats in these. So it could be argued that there is a limit as to the degree to which these trends can inform our analysis of the likelihood of Labour making significant gains at the next general election. What these patterns do highlight is the importance of candidate selection in ‘rural’ constituencies – selecting the right candidate, either from within (Penrose in Westmeath) or outside (Kemmy, Bree) the party ranks, helped the party make significant gains in 1992 on a par to those experienced in the Dublin constituencies.

One further lesson offered by an analysis of the Spring Tide election is the importance of running the right number of candidates. As the table above shows, the number of votes won by the party exceeded the quota in a number of constituencies – most of which (with exceptions of Dublin North East and Dublin South West (the party won two seats in both of these constituencies) as well as Kildare North) were contested by just one Labour candidate. This effectively meant that the Labour surpluses in these constituencies (amounting to as much as 7,317 votes in Dublin South and 6,058 votes in Dublin North) were wasted votes for the party, going instead to help in the election of candidates from other parties (most notably, Trevor Sargent in Dublin North). In all, 46,606 votes cast for Labour (14% of the total Labour vote) in this election ended up as surplus votes, effectively wasted to the party – in Dublin, the number of surplus votes amounted to 23,340 votes, or 19% of the total number of votes cast for Labour in this region. Had the party run extra candidates in Dublin South and Dublin North then they would have won second seats in these constituencies (and possibly also Carlow-Kilkenny, Dublin South Central, Limerick East and Wicklow with good vote management and some luck). On this basis, it is argued that the party need to run two candidates in a number of their stronger constituencies (and possibly even three candidates in strong five-seat constituencies, such as Dublin South Central) in order not to miss opportunities that may be provided for seat gains by a significant Gilmore Gael in 2012.

However…there is one other historical precedent that needs to be considered, namely the 1969 election where it could be argued that Labour lost seats by running top many candidates. In a “Seventies will be Socialist” burst of optimism Labour ran 98 candidates (only two of whom were female!). The clatter of lost Labour deposits from that election can still be heard even to this day… Despite increasing the party’s share of the national vote by 1.7%, Labour ended up losing four seats in this election. Urban-rural variations very much came to play here. In Dublin, the Labour vote increased by 44,825 (by 8.7% in percentage terms) with most of these gains in Dublin coming at the expense of Fianna Fáil and Labour won an extra four seats. Outside of Dublin, however, the number of votes won by the party actually declined, despite Labour running more than twice the number of candidates that they had run in the 1965 election. Labour lost eight seats in constituencies outside of the capital, with six of these losses in Munster and Cork accounting for three of these. Were these losses down to Labour running far too many candidates? When the actual constituency results are studied, the fact emerges that, with the exception of Mid Cork (and possibly also Waterford), there were no constituencies where seats were lost because the Labour vote was split between too many candidates – no constituencies where the total Labour vote exceeded a quota and the party failed to take a seat. The main less for Labour instead could be that the right candidates were not selected – far too many weak candidates (who failed to win more than 1,000 votes) ran for the party in this election. Overall, the rural seats were lost, not because of the rather over-ambitious candidate selection strategy, but because of the extent of the swing against the party in many rural constituencies, sparked no doubt by the “Red Bogey” tactics used by Fianna Fáil against Labour in that election;

“Like the United States and France signs of radical upsurge in the Labour Party were answered with a conservative backlash from rural Ireland that none has suspected was so strong and indeed so widespread. Suggestions about Communist influence in the Labour Party made by some Fianna Fáil speakers to rural audiences affected the country votes. It looks now that the allegations of Communism against (Conor Cruise) O’Brien were designed more for rural than for urban consumption.” (The Irish Times, 20 June 1969; p.10)

As well as the importance of getting in place the right candidates, the other main lesson for Labour from 1969 is that, even given their current low standing in the polls, Fianna Fáil will not give up power without a fight (albeit potentially not as dirty a fight as that fought in 1969?) and Labour will need to be ready to respond in turn, otherwise the Gilmore Gale may ultimately prove to be more akin to a Clegg Cypher.

To conclude, the experiences of 1969 and 1992 suggest that if a Gilmore Gale is gusting come the next election, then the strongest gusts will blow across the Dublin political landscape. The 1992 experience warns that the party must be ambitious in its candidate selection policy; otherwise it may miss out on potential seat gains simply by not running a sufficient number of candidates. The experiences of 1969 and 1992 both suggest that the recruitment of high profile candidates from outside the party ranks may offer a means of establishing the party in its weaker constituencies, although this is by no means a foolproof tactic (as in the case of Labour’s recruitment of Independent, and former Clann na Poblachta, TD Jack McQuillan in Roscommon, who then proceeded to lose the seat he had held since 1948 in the 1965 election). Finally the 1969 case may point towards the dangers of running too many candidates, but it more pertinently greater stresses the importance of selecting the right type of candidates while, again, illustrating the potential resistance of a rural audience to a resurgent Labour tide.

Pingback: Red C Poll 27 June: How Do Figures Translate Into Seats? « politicalreform.ie